Gainesville serial killer: How a woman in Louisiana helped break the case of 5 student murders in Florida

Watch the full story on "20/20," streaming now on Hulu

GAINESVILLE, Fla. -- Cindy Juracich was on a trip through the Florida Panhandle in August 1990 when she heard a news report about a grisly string of murders. They immediately made her think about a man from her Louisiana hometown church who used to spend time with her and her family.

That man, Danny Rolling, had told her that one day he was going to leave Shreveport, where they lived.

"He always told us ... ' One day, I'm going to leave this town and I'm going to go where the girls are beautiful and I can just lay in the sun and watch beautiful women all day,'" Juracich said.

Over the course of three days, police in Gainesville discovered the bodies of five college students, a man and four women. Three of the women had been raped and one had been decapitated. All of them had been stabbed to death and some were left in sexually provocative positions.

The murders were eerily similar to three others that had occurred in Shreveport in November 1989. She said she thought of Rolling, who, just a few months after the murders in their community, said something deeply disturbing to her then-husband, Steven Dobbin.

"He'd come over every night for a while, and then one night, Steven came in and he goes, 'He's got to go,'" Juracich said.

Dobbin told her that Rolling had told him he had a problem, Juracich said.

"I said, 'What kind of problem,'" Juracich said, "[and Steven said], 'He likes to stick knives into people.'"

Juracich said she dismissed these comments when she heard about them because she didn't want to believe that Rolling could be responsible for the triple murders in Shreveport. But news of the Gainesville murders haunted Juracich and, in November 1990, she decided to contact police on a hunch that Rolling was connected to the murders in both cities.

"It would not let me rest," she said. "One day, I picked up the phone, I called Crime Stoppers, and I said, 'I think there's one guy y'all need to investigate -- Danny Rolling.'"

Watch "20/20" FRIDAYS at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

By the time she reported Rolling, police had already arrested another man who they believed to be a suspect in the Gainesville murders. Ed Humphrey had been arrested and charged with assaulting his grandmother, but investigators were taking a hard look at him for the student murders as well.

Don Maines, an investigator on the case with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, said they received several tips pointing to Humphrey, then 18. He was known to carry knives, had been off his medication for a mental health disorder and had visible scars on his face from a car accident.

Humphrey was arrested just days after the murders and held in jail on a $1 million bond. Former state attorney Rod Smith said that when investigators then searched his home, they found magazines about knives, guns and girls.

(Edward Lewis Humphrey was an early suspect in the case of five grisly murders of college students in Gainesville, Fla. Daniel Rolling was eventually convicted of the killings, but Humphrey was never officially cleared by the police.)

"We had a lot of physical evidence that, according to our technology at the time, placed Ed at some of the scenes," Maines said. "Some fiber, some hairs. They couldn't say definitively it was Ed's hair, but they couldn't say it wasn't."

Three days, five murders

Sonja Larson and Christina "Christi" Powell were new students at the University of Florida in 1990. Alison Emery, Powell's high school best friend, said she was so excited to be moving into the next phase of her life. Those who knew Larson said she was a sweet girl, but reserved, and that she liked to work with children.

The new students had met each other during the summer and decided to be roommates, ultimately finding an apartment off-campus in a complex called Williamsburg Apartments.

Larson's mother, Ada Larson, said she "hated the fact" that her daughter would be living off-campus, but all the dormitories were full. Sonja Larson and Powell's families became unable to reach them just days after they moved in.

"We had no way of reaching her," Ada Larson said. "The phone hadn't been installed yet. She hadn't called us ... and, finally, the Powells, who lived closer, went over there."

On Aug. 26, 1990, Emery said Powell's parents arrived at the apartment and banged on the door. Without a response, they asked a maintenance worker at the apartment complex for help. In police audio recordings, he could be heard asking police to accompany him at the request of his manager.

Betty Curnutt, the manager of the apartment complex, said she was standing behind the worker when he broke down the door and that a police officer was behind her.

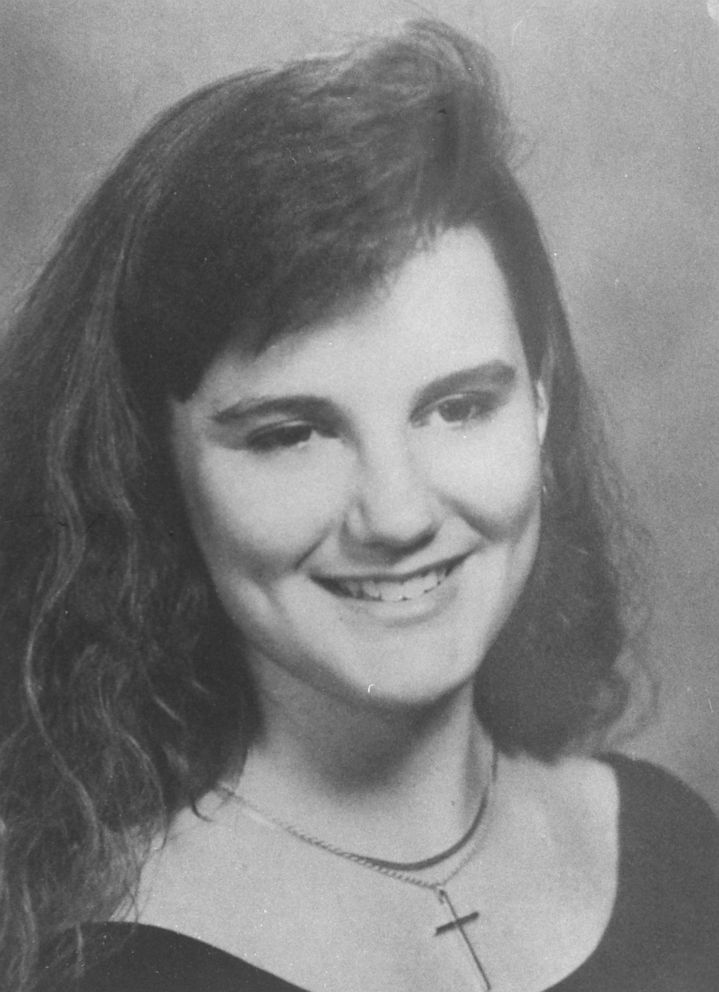

(A high school portrait shows Christina Powell, who, along with roommate Sonja Larson were the first victims of the serial killer at the University of Florida campus.)

"When he went in, I followed him in the apartment and I saw the young lady on the bed. You could see [she was] in a bad position, and I just turned around and walked out," Curnutt said. "My maintenance man, unfortunately, ran down the stairs screaming, 'Oh my God,' and came out and threw up. And the sad, sad part about it is that we had the parents behind us on the stairs."

The officer, now-retired Det. Sgt. Ray Barber, called for backup and with more investigators on the scene, they found Powell dead on the first floor of the apartment. She had been raped and stabbed multiple times and had been mutilated. Sonja Larson's body was found on her waterbed on the second floor, with stab wounds in her arms and torso.

Journalist John Donnelly, who covered the story for the Miami Herald, said the officers noticed the unusual way in which Sonja Larson's body was posed. All her clothes had been taken off, he said, and "she was lying back on the bed with her feet on the floor and her hair fanned out."

(Eighteen-year-old Sonja Larson was among the victims of the so-called Gainesville Ripper, Danny Rolling, in Gainesville, Florida, in 1990. Rolling confessed to the murder of Larson and four others and was executed in 2006.)

"I screamed," Ada Larson said about discovering her daughter had been killed. "My husband didn't know what was happening. We just got in the car and headed for Gainesville. I had to have my husband stop at the side of the road, and I looked outside and the stars were shining. I just looked at God, and I said, 'God, why? How could this possibly happen? Why did this happen?"

In the aftermath of the murders, investigators discovered some highly unusual details at the scene. Maines said they found out that the suspect had broken in by wedging a screwdriver into the door jamb. One woman had also been found with soap on her body and the perpetrator had used duct tape on both of the victims, but the tape had been removed.

"We think that was in an effort to keep investigators from discovering DNA, blood types, fingerprints," Maines said.

Wayland Clifton, the former chief of police of the Gainesville Police Department, who also visited the crime scene, said his greatest concern while driving home that night was that the suspect would commit more murders. His premonition came true the next day.

Christa Hoyt was an aspiring police officer who'd been working part-time at the Alachua County Sheriff's Office while going to school, according to Gail Barber, the first officer on the scene of her murder.

After she failed to show up to work on the night of Aug. 26, 1990, Det. Legran Hewitt said they dispatched Barber and another officer to Christa Hoyt's home. She was found raped, stabbed to death, mutilated and beheaded. Her body had also been arranged in a posed position, sitting with her feet on the floor and her torso slumped forward, Donnelly said.

"I did not want to see that young lady that meant so much to me. I did not want that to be what I carried in my mind of her for the rest of my life," Barber said.

(Nineteen-year-old Christa Hoyt was among the victims of the so-called Gainesville Ripper, Danny Rolling, in Gainesville, Florida in 1990. Rolling confessed to the murder of Hoyt and four others and was executed in 2006.)

Hoyt's stepmother, Dianna Hoyt, said she and her husband, Gary Hoyt, had a "very hard time" processing what happened to their daughter.

"My husband would just sit and say ... 'Just tell me she died right away. Tell me she did not suffer.' These police officers knew Christa ... they told Gary she died right away from the first stab, which was the truth ... but there were many hours before that."

Tracy Paules and Manny Taboada were found dead the next morning, on Aug. 28, 1990. The two 23-year-olds had been close friends since high school and had just begun living together. He had dreams of being an architect, his brother, Mario Taboada, said. She was hoping to become a lawyer.

Authorities believe Taboada was the first to be attacked after the killer broke into their home, and that they fought for some time before Taboada was killed by multiple stab wounds.

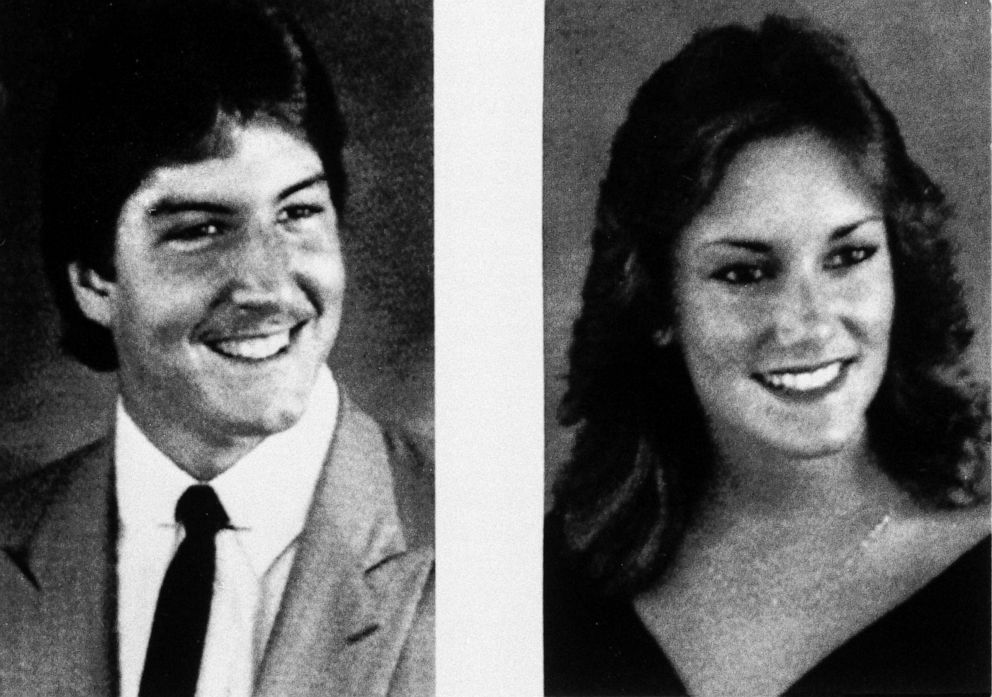

(Manuel Taboada, left, and Tracy Paules, right, are seen in undated photos. The roommates and University of Florida students, were found dead Aug. 28, 1990, in their Gainesville, Fla. apartment. Danny Harold Rolling pleaded guilty to their murders and three other people in Gainesville in August 1990.)

Police found Paules on their living room floor. Like the previous murders, Paules, who'd been raped, was found posed and she had soap on her lower body as well as tape residue on her wrists and mouth.

"All I want to know [is] what was she thinking. What fear did she have going through her mind?" said Laurie Lahey, Paules' older sister. "Was she thinking of me? I can't help it, that's what I'm thinking ... but the terror ... I can't get past that."

Finding the suspect

As concerns of a killer on the loose mounted, police were inundated with calls from concerned parents. Some had already begun to move their children out of the city, which is busiest during the school year. The magnitude of the murders sparked national media attention, and Gainesville police and the Alachua County Sheriff's Office called in agents from around the state to help with the investigation, Maines said.

Along with the similarities in which the victims were killed, there were other patterns investigators noted. The killer would enter the homes through the back doors, and each home was near a wooded area, which "allowed the killer to operate, to get in without being noticed," Donnelly said.

These details were important because, on the day of Christa Hoyt's murder, police also responded to a robbery at a bank a half-mile away from her home. During the robbery, a teller had slipped a red dye pack into the bag of money, and later on that night, an officer noticed a man walking into a wooded area, Hewitt said.

He said the officer tracked the man to a campsite. While the man had gotten away, the officer found a screwdriver at the campsite, along with the bag of money defaced by the dye and a cassette player with a tape inside. Although police had collected the evidence, at the time, they did not connect the bank robbery to the student murders because a gun was found at the campsite and the murders didn't involve a gun.

They didn't listen to the tape until months later. Yet, it would later prove crucial to finding out who the Gainesville murderer was.

As they investigated the case, police grew convinced that Ed Humphrey might be their most likely suspect.

But there was one major problem for investigators: Even though DNA testing technology was still in its infancy, investigators were able to determine the suspect's blood type through semen left behind at all three crime scenes. They found that the suspect had type B blood, but Humphrey's blood was type A.

Humphrey was still in police custody when investigators discovered a cold case in Shreveport, Louisiana, that had striking similarities to the murders in Gainesville. On Nov. 4, 1989, William Grissom, 55, his 24-year-old daughter Julie Grissom and his 8-year-old grandson Sean Grissom were killed in his home in the Louisiana city.

In Shreveport, Maines found that Julie Grissom's body had been posed in a similar position to some of the women killed in Gainesville. She also had tape residue on her body and vinegar -- rather than soap -- which was used to clean her body.

Scott Grissom, the son of William Grissom, brother of Julie Grissom and father to Sean, said they were killed just a week after his wedding, on his first day back at work from his honeymoon.

"Knowing what happened, I can't erase that out of my mind, and nobody should have to go through that," said Scott Grissom.

Maines said they tested the body fluids from the perpetrator in Shreveport and found that this person also had type B blood. He called the match to the evidence in Gainesville a "revelation" in the case.

It wasn't long after Maines' trip to Shreveport that Juracich called Crime Stoppers to report Danny Rolling. The son of a police officer and an aspiring country music singer, Rolling had spent a couple years in the U.S. Air Force before beginning a career of crime. He was convicted of armed robbery in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi for several grocery store robberies, and spent most of the 1980s in prison.

Scott Grissom said he didn't know Rolling but he learned that Rolling had lived with his parents about a half-mile away from his father's house. However, Rolling was "unwelcome" at his parents' house, Juracich said, especially if his father was there.

Three months before the Gainesville murders, in May 1990, Rolling and his father had an argument in which Rolling's father chased him out of the house at gunpoint, Hewitt said. Then, Rolling came back with his own gun and shot his father in the face, state attorney Smith said.

"It was a small-caliber gun, and the father survives it, but not without permanent damage," Smith said.

Maines said Rolling fled the home after police issued a warrant for his arrest.

Once Florida investigators realized that Rolling had multiple convictions for armed robbery, they realized he could have also been responsible for the bank robbery that occurred on the day that Christa Hoyt's body was found. They returned to the evidence locker, where the gun, screwdriver, bag of money and cassette player had been stored. Finally, they listened to the tape.

The tape contained recordings of a man talking and singing, Hewitt said. In one of the songs, the man sings, "Mystery rider, what's your name? You're a killer, a drifter, gone insane."

Hewitt said the man also talked to his family, about life and how he felt he went down the "wrong road." Smith said Rolling also talked about the best way to kill a deer.

Then, at one point, the man on the tape says his name: Danny Harold Rolling.

"That was exciting," Hewitt said. "It didn't matter what the lyrics were or what he was saying at that point."

"If we had played the tape before, we would've had this guy three months ago," Maines said. "But, for some reason, somehow, that tape escaped us, and I'll freely admit it."

The investigators didn't have to search far for Rolling; he had already been detained 40 miles south of Gainesville, in Marion County Jail, where he was being held for another robbery he'd committed at a supermarket 10 days after Paules' and Manny Taboada's bodies were found.

They subsequently discovered that Rolling had type B blood just like the suspect in both the Gainesville and Shreveport murders.

A murderer is brought to justice

On Nov. 15, 1991, Rolling was charged with five counts of first-degree murder in connection to the college students' deaths in Gainesville. He was facing the death penalty.

Before he could stand trial for the murders, however, Rolling was convicted on federal bank robbery charges, Smith said.

He was sent to Florida State Prison, where he met another inmate named Bobby Lewis, who was on death row for killing a drug dealer in the 1970s.

John Donvan, a former reporter for ABC News who covered the Gainesville cases, said Lewis claimed Rolling told him many of the details of the murders and that Rolling wanted to confess. Lewis wrote a five-page letter outlining the details, many of which Hewitt said "only the killer knew."

Investigators wanted to confirm the details of Rolling's confession, so they arranged a meeting, but Rolling insisted that Lewis be present as well to act as his mouthpiece.

So investigators sat with Lewis and Rolling and had Lewis answer questions for Rolling. After Lewis told the investigators what Rolling had told him, investigators would then ask Rolling if what Lewis said was correct. Rolling's affirmations were caught on tape.

"It was important because he was participating in the confession," Hewitt said.

The questioning elicited new details about the murders. Hewitt said they learned that Rolling had returned to the crime scene after killing Christa Hoyt because he thought he might've left his wallet there. It was upon revisiting the scene that he decided to decapitate her.

"I've never been told nothing in reality, I've never read nothing in a Stephen King novel ... that comes close to what the reality is of what this man did," Lewis said.

They also learned that as Rolling fought with Manny Taboada, Tracy Paules heard the commotion and came into Toboada's room. When she saw Rolling, she ran back to her bedroom, where she tried to lock her door. However, Rolling was able to break through it.

"Tracy asked him, 'You're the one, aren't you?'" Donvan said. "And he said, 'Yeah, I'm the one.'"

As the questioning went on, Rolling began to say he'd "dealt with different personalities all my life." He told investigators about two of his darker personalities.

The first was named Ynnad -- "Danny" spelled backward. He described Ynnad as a bad person, but not evil. The second, more sinister personality, was named "Gemini" and Rolling blamed him for his deadliest acts.

"I didn't buy it," said forensic psychologist Harry Krop. "This was Danny looking for something that would make what happened more dramatic and ... minimize his own culpability by saying, 'The devil made me do it.'"

Although they had a confession for the Gainesville murders, investigators were not able to get Rolling to admit to the Shreveport murders during their questioning.

Rolling also made it clear to investigators that he acted alone and that Ed Humphrey had no involvement in the student murders. Authorities subsequently cleared Humphrey of any involvement in the murders. He was released from jail 10 months after he'd assaulted his grandmother.

"It was the desperation of the time, and the need to get that guy," Smith said. "We made a mistake."

Rolling's trial for the five student murders began on Feb. 15, 1994, nearly four years after he killed the five students.

(Danny Harold Rolling appears at his trial in Tampa, Fla., Feb. 13, 1994. Rolling pleaded guilty to the serial killings of five young people at the University of Florida in Gainesville.)

For the families of those students, being there to see him at trial was crucial.

"I wanted to represent [Tracy]," said Lahey, Paules' sister. "I kept saying to myself, it's the last thing I can do for her."

"I wanted to know every little detail," Ada Larson said. "I had to know ... what Sonja went through. I had to know it."

Dianna Hoyt said they held hands as Rolling was brought into the court. Lahey said seeing this man "who destroyed my life" made her feel "frozen to the chair."

State Attorney Rod Smith said that before the court could proceed with the case, Rolling and his defense lawyer stood up. Rolling wanted to address the court.

"Your honor, I've been running from first one thing and then another all my life," Rolling said. "But there are some things that you just can't run from and this being one of those."

Rolling pleaded guilty to all counts but, because he was facing the death penalty, a jury was still required to hear the evidence and make a recommendation on punishment to the judge: life in prison or death.

"Every time they'd mention [Tracy's] name, it was like a punch in the head," Lahey said.

Rolling's defense presented mitigating factors for why he might have committed the murders, including his troubled history with his father. Witnesses testified to the abuse they'd seen.

Claudia Rolling, Danny Rolling's mother, also testified. When asked if she ever felt that her husband was treating her son inappropriately, she said, "Sure, I guess."

"Sometimes he would put him up against the wall ... the marks of his fingers would be there and he shook him a lot of and sort of scared me," Claudia Rolling said.

To Christina Powell's friend, Alison Emery, said the defense's strategy was a "slap in the face."

"It was like, here's a reason he killed the person you loved," she said. "So, let's take it easy on him."

Dianna Hoyt said she didn't believe "any of it. There's many people that have abusive parents. They don't go out and commit crimes like this."

Prosecutors also attacked Rollings' claims that he had multiple personalities and that he was overtaken by his evil "Gemini" side when he murdered his victims. This argument, Smith claims, was purely based on a character in the film "Exorcist III," which Danny Rolling had admitted to watching on the week he murdered in Gainesville.

"He just stole that and used that [as] part of his story," Smith said. "Danny committed these crimes for one reason only -- he loved it."

Ultimately, the jury recommended five death sentences for Rolling and the judge agreed, sentencing him to execution.

Following the sentencing, Manny Taboada's brother, Mario Taboada, stood up and shouted, "You're going down in five. Do you understand that? In less than five years. We have the last say. We will prevail. Our children's names will be remembered over him."

A judge ordered him removed from the court.

"I did that at the time because I read that serial killers like to be in control," Mario Taboada told ABC News. "So I wanted to have the last word."

Danny Rolling was put to death by lethal injection on Oct. 25, 2006. Prior to his death, he spoke to a pastor and handed him a note. On it, he admitted to killing 55-year-old William Grissom, 24-year-old Julie Grissom and 8-year-old Sean Grissom in Shreveport.

"[Investigators] were 100% sure he was the one that did it," Scott Grissom said. "And honestly, they advised that he'd die much faster in Florida, and I said, 'Well, leave him there. Leave him there.'"

For the family members of the Gainesville victims, it was another moment in this long and heartbreaking story.

"I wanted to be there in the front row if I could. I knew, until he was gone, I couldn't really start my life again and be me," Lahey said.

The families whose loved ones were murdered in Gainesville say they are grateful for the simple memorial that remains today. On a stretch of road running through the city, there is a graffiti-covered wall. One piece of this wall has remained unchanged for more than 30 years: The section where the names of all five victims are painted in remembrance: Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel Taboada, Tracy Paules.

"It's a place for all of us families to go ... and see their children's names still living there," Dianna Hoyt said.

"They're gone but their memory has to always endure," Mario Taboada said. "In a way, talking about [Manny], as I do sometimes with those who knew him ... they're kind of alive for that moment, and so, it's comforting."